Evolution of Jiggly Stuff

01 Jan 2022I like positing hypotheses that are completely unverified and poorly examined. Why? Because it’s easier to play with ideas when you don’t have to check your work. 🤣 Here are two somewhat related hypotheses about how evolution has made two very different jiggly things more durable and resistant to distress: your brain and trees.

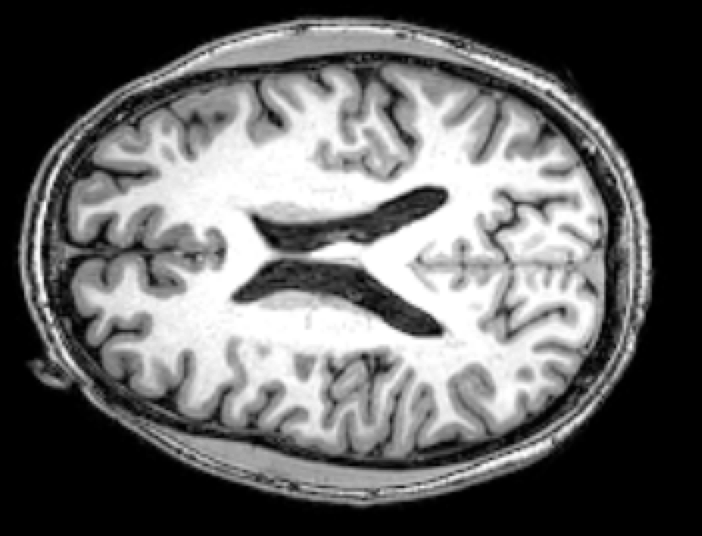

The Brain and its Ventricles

Look at this beautiful brain. It’s mine! But for the sake of this conversation, notice what’s missing from my brain… all the stuff in the middle. That’s ok though, the missing part are the ventricles of the brain, they’re supposed to be there… ur, not there… and I propose that the missing part provides a structural benefit. Why? Well the brain is effectively a big block of super important thinking tofu, and if the thinking tofu breaks, then it doesn’t work so well. But the problem is that humans have historically been a bunch of nuckleheads. We break boards over our heads and devise silly sports where we ram our heads into one another at high speeds. For some sports we just directly punch one another in the heads. This is where the ventricles are important. If the ventricles were instead filled in with brain material, then I posit that a sudden strike to the head, especially a torsional strike, would result in maximum sheer right in the middle of the brain and it would easily rupture the thinking tofu. But if there is no material in the middle of the brain, then the stress that would be focused in the middle of the brain is instead distributed across the surface of the ventricles. Thus the thinking tofu is much less likely to get fractured when you are struck in the head. Fantastic, now we can enjoy our violent sports and worry about the damage we’re doing years later.

Trees and their Branches and their Twigs

During bad storms, (of which Tennessee has had quite a few recently), I enjoy watching the way the wind blows the trees because I suspect that this is another example of how nature has evolved towards building a structure that is robust. Twigs vibrate; they’re like springs. And just like springs, they have a natural frequency. And if you happened to excite the twigs at some point near to their natural frequency, then the tendency would be for the twig’s vibrations to increase in amplitude. (For the sake of argument, I’m ignoring the effects of damping.) Twigs are attached to limbs, limbs are attached to larger branches, and branches are attached to the trunk. Now consider an extreme situation: what if the trunk, branches, limbs, and twigs in a tree were structured such that the natural frequency at any level of the hierarchy was tuned to be harmonically resonant with the previous level? In this situation, if a breeze caused the trunk of the tree to gently sway, then this would cause the branches to oscillate in a higher frequency resonance, which would in turn cause their limbs to oscillate at a higher frequency, and then cause the twigs to vibrate violently. If there was insufficient damping, then a persistent breeze with the right frequency content would cause the tree to literally shake itself apart. But, evolution has ensured that trees aren’t tuned this way. Any tree that was so “perfectly” tuned would also be more likely to lose branches and therefore be less likely to produce offspring. Instead, I propose that evolutionary pressures have tended to optimize the structure of trees toward the opposite situation. Rather than each level being in perfect resonance with the lower level, my bet is that they have evolved to be perfectly out of resonance with lower levels. That is, when the trunk vibrates, it sets the limbs into motion in such a way that the energy is quickly dissipated from the tree, making it less likely for the trunk to break or for large limbs to break out of the tree. Bradford Pear Trees (pictured above) obviously didn’t get the memo.