Neuroscience Penny Chat with Stephen Bailey

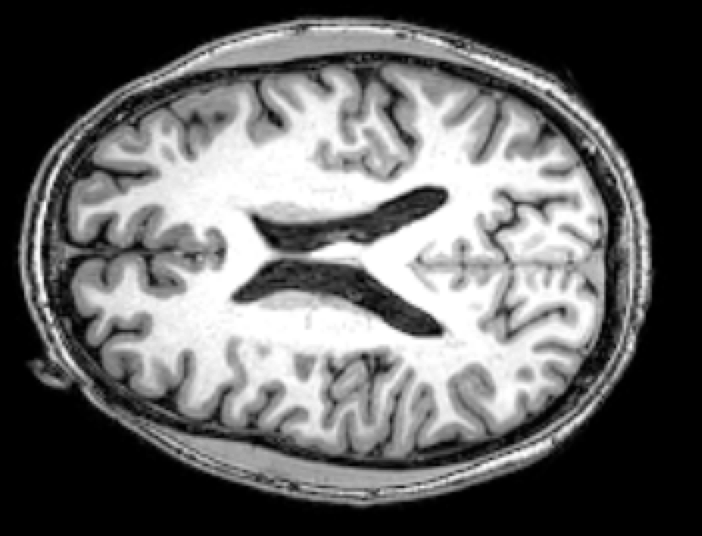

27 Sep 2017Last week I took part in a Medical Imaging study at Vanderbilt in Stephen Bailey’s laboratory and lookey at this:

… it’s my brain! Yeah, literally, that is my brain! And if you want to know what I think… I think it’s a beautiful specimen!

So this week I followed up with Stephen and learned more about his work and about neuroscience in general. Here are some of the high points:

How does an MRI work? And what is it used for?

Magnetic Resonance Imaging makes use of a massive magnetic to detect changes in the distribution of metal in your brain. “Metal in my brain?!” Yep, your blood carries nutrients including trace amounts of iron into your brain. So really the MRI is picking up on changes in how blood is being routed to your brain. And by watching blood flow in the brain you can actually see which parts of your brain that are being used most arduously.

So most brain studies with MRIs (including mine) follow a pattern similar to this: First they stick you in the machine and get a baseline “picture” of your brain. This isn’t a picture in the normal sense, it’s actually a 3D data set that in my case was 256x256x184 “voxels”. (So if you want to see a different slice of me, you can!) Once they have a baseline picture then they make you do some repetitive task that taxes a certain part of your brain and they take a follow-up picture and see what’s changed. In this way neuroscientists have been able to closely isolate the parts of your brain that are involved in certain cognitive and sensory tasks.

Stephen’s Brainy Research

Now direct your attention again to the beautiful brain at the top of this post. The brain is composed largely of two types of tissue:

- Grey matter (grey in the photo) covers the outside of your brain and is responsible for most of the computation that happens in your head.

- White matter (white in the photo) is on the interior of your brain and serves to connect areas of the brain and route information between them.

MRIs are typically used to measure activity in the grey matter. The changes in blood flow in white matter are much more subtle and thus harder to detect. This is very unfortunate because typical MRIs only give a partial picture of what is happening in the brain. A more complete picture would both indicate the parts of the brain are doing computation (grey matter) and also how the information is being routed between the computation centers (in white matter).

This is exactly what Stephen is working towards with his research. He is refining the MRI techniques and data processing so that we can have this more complete picture and understand how parts of the brain are interconnected.

Why am I so Interested in the Brain?

What!? You’re not?! It’s like a blob of magic jello that can process information and learns things. Hook it up to a human meat vehicle and watch it go! It learns to walk upright. It can take in visual information from stereo cameras and avoid obstacles. It can capture and process information and use it again later … you see where I’m going.

One thing I would really love is to understand just how we learn and how we think. I was once of the opinion that only God was allowed to make thinking things. But these days I’ve softened my stance. Maybe we can make a truly intelligent system. (God is still in charge of making conscious things… but let’s save that for a different discussion.)

One of my longstanding dreams is to understand learning and thinking to the point where I can describe the necessary and sufficient requirements for building such a system. And then I want to build it. (Yeah, yeah… seems like a long shot, but let me dream.) So part of my discussion with Stephen was describing my thoughts about learning and cognition and seeing if my understanding was valid or was science fiction. I was happy to find out that I wasn’t too far off! One thing that Stephen made clearer to me though is that an MRI isn’t quite the measurement system that I am looking for with my research. An MRI isn’t really watching you think, it’s more like watching which parts of your brain you use to think. The timescales of thought are in tens of milliseconds while the timescales of MRIs are in tens of seconds. So I also learned a little more from Stephen about the devices out there which can be used to “measure” thought: the EEG and the MEG.

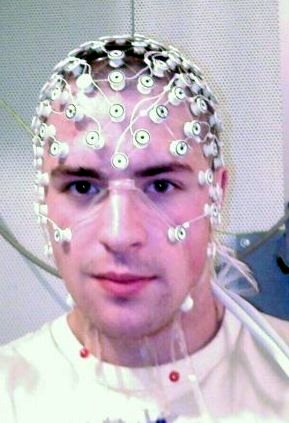

The Electroencephalography (EEG) is basically a net filled with electrodes that you stick to your scalp.

This device can measure the electrical impulses through your brain at a very high bandwidth - certainly as “fast as thought”. Unfortunately the spatial resolution is pretty horrible so it’s difficult to isolate exactly where the impulses are coming from.

Between EEG and MRI is Magnetoencephalography (MEG).

MEG measures the induced magnetic fields created from electronic circuits in your head (aka “thought”). However the capture rate isn’t as fast as EEG and the spatial resolution isn’t as fast as MEG. So it really is an intermediate solution. Oh yeah… and there’s only a handful of these expensive machines in the world.

Conclusion

So while I haven’t yet unraveled the mystery of how we think, I did learn a lot! An maybe I even got a little bit closer. Thanks Stephen for your time. Let’s make sure to do it again often.

Penny University

The above conversation was from a “Penny Chat”. Are you interested in learning with others? Come check out our community an find more people like you.