EARRRL – the Estimated Average Recent Request Rate Limiter

18 Mar 2021You’ve got a problem: a small subset of abusive users are body slamming your API with extremely high request rates. You’ve added windowed rate limiting, and this reduces the load on your infrastructure, but behavior persists. These naughty users are not attempting to rate-limit their own requests. They fire off as many requests as they can, almost immediately hit HTTP 429 Too Many Requests, and even then don’t let up. As soon as a new rate limit window is available, the pattern starts all over again.

In order to curtail this behavior, it would be nice to penalize bad users according to their recent average request rate. That is, if a user responsibly limits their own requests, then they never get a 429. However if the user has the bad habit of constantly exceeding the rate limit, then we stop them from making any more requests – forever … no new windows and no second chances… that is until they mend their ways and start monitoring their own rate more responsibly. Once their average request rate falls below the prescribed threshold, then their past sins are forgiven, and they may begin anew as a responsible user of our API.

Introducing the Recent Average Rate Limiter

Drawing inspiration from the Exponentially Weighted Moving Average, I propose EARRRL, the Estimated Average Recent Request Rate Limiter. EARRRL estimates the user’s recent request rate and rejects requests for users who’s request rate exceeds the specified threshold. It gets rid of the notion of rate limit windows, and instead keeps a persistent estimate of a user’s request rate so that an abusive user can’t just start offending again as soon as the next rate limit window is available. Just how this works gets kinda mathy, which is why I’ve authored the aptly named companion post. But for this post we’ll focus on more practical aspects of implementation and application.

Let’s say that you are rate limiting an API endpoint called send_yo which requires authenticated access. Every user will be associated with their own EARRRL rate limiter. So, at the beginning of a request you retrieve the rate limiter associated with the current user (or otherwise create one), and you ask it “should this user be allowed to make a request?” In code, it would look something like this:

def send_yo(request, recipient):

rate_limiter = EARRRL.get_or_create(user=request.user.id)

if rate_limiter.is_rate_limited():

# abusive user has exceeded their "Yo" sending limit

return render(request, '429.html', status=429)

actually_send_the_yo(recipient)

Internally, is_rate_limited will quickly evaluate the user’s recent request rate, update the rate based upon the current request, and then return whether or not the user has exceeded the prescribed rate.

Watching EARRRL in Action

At the bottom of this post we will implement EARRRL in Redis, but before we get there, let’s motivate that conversation by demonstrating some of EARRRL’s more interesting qualities.

Convergence

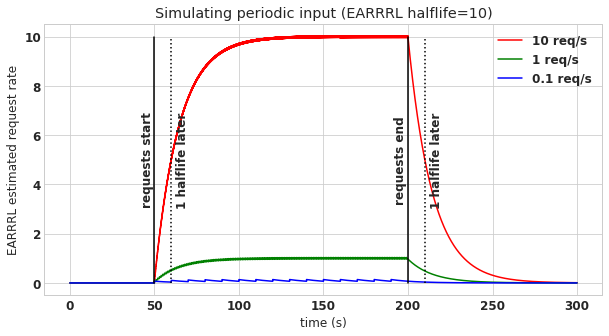

It is important that EARRRL can correctly estimate a user’s recent request rate. To demonstrat that this works correctly, let’s consider the scenario where at \(t=50\text{s}\), three different users being making sustained periodic API requests, and then at \(t=200\text{s}\) they stop. The user represented in red makes 10 requests per second, the green user makes 1 request per second, and the blue user makes one request every 10 seconds. The corresponding lines in the following figure represents the EARRRL-estimated average request rate. You can see that shortly after the requests begin, EARRRL converges to the true rate, and then in the same period of time after the requests stop, EARRRL converges back to zero.

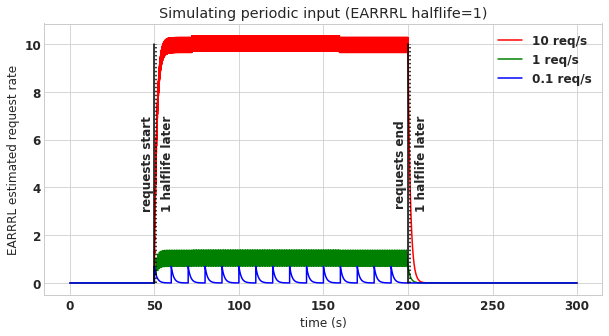

The EARRRL for this figure uses a half-life of 10 seconds, and you can see evidence of this in the plot, because 10 seconds after the requests start, the estimates rises to half of the true request rate. Similarly 10 seconds after the requests end, the estimates decay halfway back to 0. Because of this, you can use the half-life to control how quickly the estimator converges to the true request rate. However beware, there is a tradeoff between half-life and estimate error, the shorter the half-life, the higher the error. As an example, here is a plot of the same scenario but with a half-life of only 1 second.

There is much more detail about why this tradeoff exists in the companion post, but fortunately you probably don’t have to care too much. Generally it’s not super important for EARRRL to converge quickly. Rather, it’s more important that persistently abusive users get permanently banned while they continue abusing, and a long half-life should be fine for this.

Comparison Between EARRRL and Windowed Rate Limiters

Recall, my main complaint against windowed rate limiters is that, at the ending of every single window, all sins are forgiven, and the rate limit is completely reset. Spammy users rejoice, because they can just keep firing off requests as fast as they please until someone from platform health catches on and bans them. (And then they just make another account and start over again.)

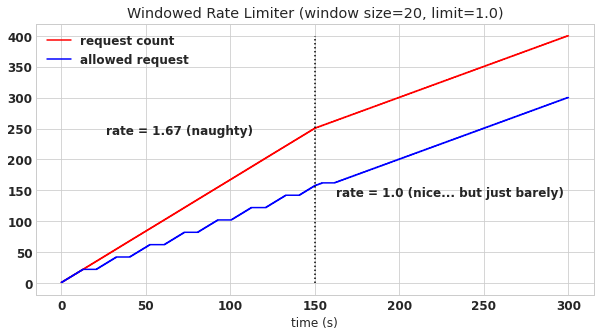

Here’s what rate limiting looks like with a windowed rate limiter. In this scenario, the abusive user initially makes requests at a rate 67% higher than our allowable threshold of 1 request per second. At the half-way point, 150 seconds, the user decides to start obeying the rate limit and sends exactly 1 request per second. The red line represents the user’s cumulative number of requests, and the blue line represent the cumulative number of requests that are permitted by the windowed rate limiter.

Can you see the pattern? Toward the beginning of every window the user quickly meets their quota of requests and gets cut off, but they nevertheless keep sending requests (e.g. the red line keeps going up). Then at the next window the process starts over again and their requests succeed. And, if you’ll notice, the overall rate of successful requests made by the abusive user is exactly the maximum allowed rate. What incentive do they have to change? None! This is no good.

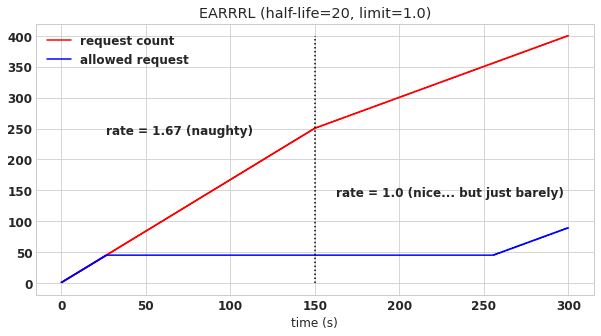

Let’s see what happens with EARRRL in the exact same scenario.

As you can see, EARRRL is more shrewed. Initially it provides the user with a longer grace period than the windowed rate limiter before cutting off the user, but then after EARRRL determines that the user plans on abusing the rate limit, it locks down and does not permit any more requests. Unlike the naive windowed rate limiter, EARRRL does not constantly forgive the user and let them abuse again. Rather, it waits. Once EARRRL the user demonstrates that they will keep their average request rate below the prescribed threshold, EARRRL allows requests to proceed again (at roughly 255 seconds in this example).

Implementation in Redis

Now since you’ve seen what EARRRL can do, I want to show you just how easy it is to implement. By the end of this blog post we’re going to have a Redis implementation that might actually be production worthy!

The language for our implementation is Lua. Why? Because Redis is the ideal technology for building EARRRL and Lua is its built-in scripting language. Here is the Lua/Redis implementation for EARRRL with a rate limit of 0.5 requests per second and a half-life of 10s.

-- parameters and state

local lambda = 0.06931471805599453 -- 10 seconds half-life

local rate_limit = 0.5

local time_array = redis.call("time")

local now = time_array[1]+0.000001*time_array[2] -- seconds + microseconds

local Nkey = KEYS[1]..":N"

local Tkey = KEYS[1]..":T"

local N = redis.call("get", Nkey)

if N == false then

N = 0

end

local T = redis.call("get", Tkey)

if T == false then

T = 0

end

local delta_t = T-now

-- functions

local function evaluate()

return N*lambda*math.exp(lambda*delta_t)

end

local function update()

redis.call("set", Nkey, 1+N*math.exp(lambda*delta_t))

redis.call("set", Tkey, now)

end

local function is_rate_limited()

local estimated_rate = evaluate()

local limited = estimated_rate > rate_limit

update()

return {limited, tostring(estimated_rate)}

end

-- the whole big show

return is_rate_limited()

This is my first time playing with Lua/Redis but I found it quite easy to work with, and even kinda fun! Again, I’ll refer you to the companion post for why this stuff all works, but for the sake of understanding the code there are a few things to notice. First, for each user we keep their EARRRL state in two variables N (roughly representing number of requests) and T (representing the time of the last request). We store these in Redis keys: If a user’s id is user_id_123, then N is stored in user_id_123:N and T is stored in user_id_123:T respectively. is_rate_limited is the main function and it works by calling evaluate to get the current estimate of the request rate (prior to this request), and then it calls update which updates the state of the estimator in Redis. Finally the decision to refuse the request is returned (true or false) along with the pre-request estimate for demo purposes below.

Now since we have the script ready, let’s upload it to Redis. Assuming you saved this script to earrrl.lua, here is how:

$ redis-cli SCRIPT LOAD "$(cat earrrl.lua)"

"cb3696c74cc51596d07646e64a17f5f2db510adb"

The SHA that gets returned is an identifier used to invoke the script. Like so:

$ redis-cli EVALSHA cb3696c74cc51596d07646e64a17f5f2db510adb 1 user_id_123

The first argument after the SHA tell Redis how many keys will be passed in, and the second argument in this case is the key, an identifier for the user that just made a request.

Does it work? I dunno, let’s find out. Let’s do an experiment that tests 2 aspects of EARRRL: convergence to the correct value and convergence rate. Here’s our test script:

$ for i in {0..70} true

do

sleep 1

echo "request # $i"

redis-cli EVALSHA cb3696c74cc51596d07646e64a17f5f2db510adb 1 user_id_123

done

sleep 10 # the half-life

redis-cli EVALSHA cb3696c74cc51596d07646e64a17f5f2db510adb 1 user_id_123

Since we are sleeping 1 second between each hit, our request rate is 1 per second. We know that with a half-life of 10 seconds, the algorithm should be about half way to this value by the 10th request.

request #0

1) (nil) <------------ this means "rate limit not exceeded"

2) "0"

request #1

1) (nil)

2) "0.064625593423117" <--- these values are the rate estimates

request #2

1) (nil)

2) "0.12483578218756"

request #3

1) (nil)

2) "0.18093794941434"

request #4

1) (nil)

2) "0.2332841604735"

request #5

1) (nil)

2) "0.28208311764286"

request #6

1) (nil)

2) "0.32757287863479"

request #7

1) (nil)

2) "0.36998350934232"

request #8

1) (nil)

2) "0.40940326068647"

request #9

1) (nil)

2) "0.44628146174133"

request #10

1) (nil)

2) "0.48060100760135"

request #11

1) (integer) 1 <------------ this means "rate limit IS exceeded"

2) "0.51262461170605"

This looks about right. Notice that at request 11 we have hit the 0.5 req/sec rate limit as represented by (integer) 1. Next we want to make sure that at steady state (say after 7 half-lives) that the value should converge to the true rate of 1.0.

request #70

1) (integer) 1

2) "0.94514712058575"

Close, but not quite. However, there is a reasonable explanation for this. Our rate evaluation comes just before we update the EARRRL state. That means that in this case, the rate estimate has had roughly 1 second to decay before it is evaluated. If we evaluate just after the update, the rate estimate will actually be a bit above 1 request per second. So this is the expected behavior. If you would like to have less error here, then a longer half-life is required.

Finally, let’s check that 10 seconds after the last request, the estimated rate has decayed to half of what it was when the requests ended.

1) (integer) 1

2) "0.50703163627721"

Yep. So it seems that it works!

The last super important ingredient in a Redis deployment is how to deal with the lifetime of the keys. With the windowed rate limiters, the keys are given a TTL of, say, 15 minutes. This is not what you want to do with EARRRL because that makes EARRRL forget past offenses and EARRRL effectively becomes an overly complicated windowed rate limiter. Instead, the keys need to reside in a LRU (Least Recently Used) cache. This way, the aggressive offenders will remain in EARRRL’s memory as long as they remain active. Using a LRU cache for EARRRL is a very natural choice because users who get expelled are expelled because they haven’t made any requests recently, and they probably have a rate limit low enough to justify being expelled anyway. This might result in some memory savings because you don’t need to track as many users. With windowed rate limiters, even the users who make only one request will have memory reserved for them for the entirety of the window period.

Conclusion

Estimated Average Recent Request Rate Limiters present an attractive alternative to standard window-based rate limiters. Whereas windowed rate limiters are permissive, allowing abusers to send a torrent of requests at every new rate limit window, EARRRL keeps a persistent estimate of the user’s rate and permanently refuse access as long as the user continues to abuse rate limits. This has some interesting follow-on implications as well. With windowed rate limiters, followup analysis is required to identify persistent bad actors and ban them. However there is nothing to disincentivize the bad actor from immediately creating a new account and continuing again in the same usage pattern. However, with EARRRL, there is no need for followup analysis, and if the user goes to the effort of creating a new user, they’re just going to immediately hit the same wall again. The only way, then, to get requests through is to be a responsible user of the API.

We also see in the last section that it is simple to implement this algorithm in Redis. So, not only should this approach be effective, but I think it’s practical as well.

What do you think? If you’re looking for all the juicy math details, then remember to check out my the mathy version of this blog post. If you have any ideas for improving this blog post or this method, or if you want to tell me that all of this already exists, or that everything is wrong, then I’m interested in that too! Ping me up on Twitter and let’s chat.