Build your own Skip List

16 Sep 2018The skip list is one of my favorite data structures.

- It can be used to implement ordered lists or sets.

- It is easy to understand.

- It doesn’t require any complex re-balancing like some of the other ordered-list structures.

- It’s fast. And all of the operations - insert, search, delete - are O(log n) on average.

Here’s my ASCII-art schematic for what a skip list might look like for a sorted list of numbers from 0 through 9. Let’s dig into how we get here.

[7]-------------------------->[6]

| |

[2]------>[1]---------------->[5]------>[3]->[4]

| | | | |

(S)->(0)->(1)->(2)->(3)->(4)->(5)->(6)->(7)->(8)->(9)->(E)

A skip list starts as a plain old linked list. To add a value to a list you start at the head and traverse node by node until you run into the first value greater than the one you’re inserting; that’s where you stick the new value. But the difference between a linked list and a skip list becomes obvious immediately. Whenever you add a new value to the linked list, there is a probability (often 0.5 or 0.25) that you “project” a node into a faster “lane”. (Time to start looking at that figure above again.) If this is the first node in the faster lane then you also create a head node at the beginning of the list that points to this fast lane node. As soon as that node is generated, there is again a probability (the same probability as before) that another new node will be projected into an even faster lane. After that node is generated, there is a probability that yet another node will be generated - and so on.

The end result after several list insertions is something like you see in the image above. When it’s time to insert a value the top “lane” allows for lookups to quickly skip over large chunks of the list until we pass the position of the value. At this point we can back up to the last node that preceded the value, jump down to a slower lane and search again for the point at which we just pass the position of the value. We repeat this until we are in the slowest lane - the bottom linked list - and then we can insert the value like we normally would as a linked list.

So let’s build one!

I’ve always wanted to build my own skip list from scratch and I finally had a chance to take a stab at it today. The code below is not completely general (I’m building this so that I can use it in a data sketch that I blog about here) but it does showcase how the data structure works.

import random

class Node():

def __init__(self, value = None):

self.left = None

self.right = None

self.down = None

self.up = None

self.value = value

def __repr__(self):

return '({})'.format(repr(self.value))

def __lt__(self, value):

if self.down:

return self.down < value

else:

return self.value < value

class StartNode(Node):

def __lt__(self, value):

return True

def __repr__(self):

return '(S)'

class EndNode(Node):

def __lt__(self, value):

return False

def __repr__(self):

return '(E)'

class SkipList():

def __init__(self, up_prob=0.5, verbose=False):

"""Skip list implementation

up_prob = probability that we extend upwards

"""

self.up_prob = up_prob

self.verbose = verbose

head = StartNode()

end = EndNode()

head.right = end

end.left = head

self.head = head

self.index = 1

def add(self, value):

if self.verbose:

messages = []

messages.append('adding {}'.format(value))

# find node to the left of value

skip_nodes = [] # the list of skip nodes above the final node

node = self.head

while True:

if node.right and node.right < value:

if self.verbose:

messages.append('\ttraverse right')

node = node.right

elif node.down:

if self.verbose:

messages.append('\ttraverse down')

skip_nodes.append(node)

node = node.down

else:

if self.verbose:

messages.append(

'\tadding {} after {}'.format(

value, node

)

)

break

# insert new node

new_node = Node(value)

right = node.right

new_node.right = right

if right:

right.left = new_node

left = node

new_node.left = left

left.right = new_node

# project upward

low_node = new_node

while True:

if random.random() > self.up_prob:

# extend upwards

projection_node = Node('s' + str(self.index))

self.index += 1

low_node.up = projection_node

projection_node.down = low_node

if skip_nodes:

left_node = skip_nodes.pop()

right_node = left_node.right

if self.verbose:

messages.append(

'\tplacing projection_node {} between left_node {} and right_node {}'.format(

projection_node, left_node, right_node or 'NONE'

)

)

left_node.right = projection_node

projection_node.left = left_node

projection_node.right = right_node

if right_node:

right_node.left = projection_node

else:

# we are projecting higher than the head node, so make a new head and a new lane

new_head = Node('s' + str(self.index))

self.index += 1

if self.verbose:

messages.append(

'\tpointing new_head {} to new projection_node {}'.format(

new_head, projection_node

)

)

projection_node.left = new_head

new_head.right = projection_node

new_head.down = self.head

self.head.up = new_head

self.head = new_head

break

low_node = projection_node

else:

break

if self.verbose:

messages.append('')

print('\n'.join(messages))

return new_node

def pop(self, node=None):

if not node:

node = self.head

while node.down:

node = node.down

node = node.right

original_node = node

if self.verbose:

messages = []

messages.append('popping node {}'.format(node))

while True:

left = node.left

right = node.right

if self.verbose:

messages.append(

'\tconnecting {} to {}'.format(

left, right

)

)

if left:

left.right = right

if right:

right.left = left

node.left = None

node.right = None

node.down = None

if node.up:

old_node = node

node = node.up

old_node.up = None

else:

break

while True:

if left is self.head and left.right is None:

if self.verbose:

messages.append(

'\tremoving head {} so that {} is the new head'.format(

self.head, self.head.down

)

)

left = self.head = left.down

else:

break

if self.verbose:

print('\n'.join(messages))

return original_node

def __iter__(self):

node = self.head

while node.down:

node = node.down

node = node.right # skip start node

while node.right:

yield node

node = node.right

I encourage you to copy paste the code into a jupyter notebook and play around with it. You’ll notice that I’ve added a lot of logging if you turn the verbose parameter on. Let’s give it a spin:

def skip_list_insert(n):

skip_list = SkipList(verbose=True)

for i in random.sample(range(n), n):

skip_list.add(i)

return skip_list

skip_list = skip_list_insert(10)

The code above creates a randomly sorted list of numbers from 0 to 9 and inserts them one at a time into an initially empty skip list. The verbose commentary is shown below. Note in the commentary that the skip nodes are labeled as things like ('s4') while the nodes that hold values are labled as things like (3). The skip list starts out as a simple linked list that holds two items, the start node (S) and the end node (E). The commentary for each value insertion follows this pattern:

- the value we are adding

- how we traverse the skip list to get to the node just before it

- adding in the value after that node

- optionally adding in one or more projection nodes into faster lanes

adding 9

adding 9 after (S)

adding 1

adding 1 after (S)

pointing new_head ('s2') to new projection_node ('s1')

adding 4

traverse right

traverse down

adding 4 after (1)

adding 7

traverse right

traverse down

traverse right

adding 7 after (4)

placing projection_node ('s3') between left_node ('s1') and right_node NONE

adding 6

traverse right

traverse down

traverse right

adding 6 after (4)

adding 8

traverse right

traverse right

traverse down

adding 8 after (7)

placing projection_node ('s4') between left_node ('s3') and right_node NONE

adding 2

traverse right

traverse down

adding 2 after (1)

adding 0

traverse down

adding 0 after (S)

adding 3

traverse right

traverse down

traverse right

adding 3 after (2)

adding 5

traverse right

traverse down

traverse right

traverse right

traverse right

adding 5 after (4)

placing projection_node ('s5') between left_node ('s1') and right_node ('s3')

pointing new_head ('s7') to new projection_node ('s6')

The end result looks like this:

[7]-------------------------->[6]

| |

[2]------>[1]---------------->[5]------>[3]->[4]

| | | | |

(S)->(0)->(1)->(2)->(3)->(4)->(5)->(6)->(7)->(8)->(9)->(E)

To make sure that the results are as expected let’s print them out

>>> nodes = list(skip_list)

>>> print(nodes)

[(0), (1), (2), (3), (4), (5), (6), (7), (8), (9)]

Perfect!

My version of the skip list also allows for deletion by node. Note that this is different than typical skip list implementation where you delete by value. When deleting by value you have to search for the node that holds that value, pull out that node, and then splice together the left and right pieces of the skip list. When deleting by node we skip the search step. But here’s an example result:

>>> skip_list.pop(nodes[5])

popping node (5)

connecting (4) to (6)

connecting ('s1') to ('s3')

connecting ('s7') to None

removing head ('s7') so that ('s2') is the new head

Pretty self explanatory I think.

I’ve also added in functionality so that if you call pop with out a node argument it will just pop off the first item in the list. In this way a skip list can be used as a priority queue.

Performance

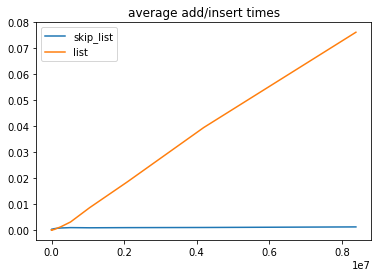

OK, so I build it… but does it really perform? Well check this out. In the plots below I’m comparing the add time of the skip list with that of a normal python list (using bisect.insort_left). The x-axis represents the number of elements in the list.

In this plot we can see that list performance scales linearly (just as the Python docs said it would) and we see that the skip list performs much much better.

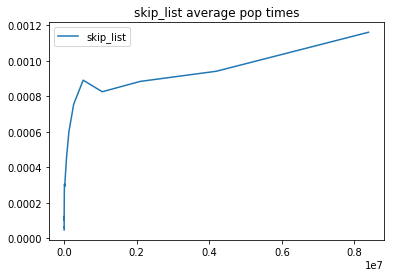

If we zoom in on the skip list performance…

…we see that, maybe ignoring some noise, the performance does appear to scale as O(log n). Great! So there it is folks… there’s a skip list and it’s awesome.

…

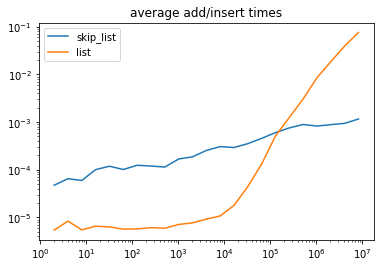

Well… just for the sake of full disclosure, let’s look at one more plot:

This is the exact same data as the first performance plot, but this time plotted in loglog. This tells just a little different story doesn’t it? You can see that for really large numbers the performance of the vanilla python list explodes. But how often do you think you’ll find yourself in a tight loop inserting items into a list that contains 80M items? What this plot tells us is that if your list has less than 50K elements you might as well just use the Python list implementation. As a matter of fact, if your list contains about 3000 elements, the skip list implementation is going to be around 20x slower!

Conclusion

Despite the poor performance of my skip list for low cardinality lists, I still think this data structure is pretty amazing. I’m sure that I (or someone much smarter than me) could reimplement the skip list in c and get much better performance. I’m confident of this because otherwise the skip list wouldn’t have found such favor among data store builders. The skip list features prominently in many data stores that I’m sure you’ve heard of: Cassandra, Lucene (e.g. Solr and Elasticsearch), Redis, HBase, and leveldb just to name a few.