Haystack Highlights

30 Apr 2018On April 10th and 11th OpenSource Connections held their first (annual I hope) Haystack search relevance conference. It was intended to be a small-and-casual, 50-person conference but ended up pulling in roughly 120 people requiring OSC to scramble to find more space. The end result was one of the best conferences I’ve ever attended. In general, conference speakers have to aim their content at the lowest common denominator so they that they don’t lose their audience. At this conference, the lowest common denominator was really high! So there was no need to over-explain the boring introductory topics. Instead the speakers were able to jump into interesting and deep content immediately.

Needless to say, I came away with a ton of good information that I’m going to put to work at Eventbrite as soon as possible.

Big Themes

In the talks that I attended there seemed to be two major threads of content. The first has to do with the maturation of search relevance as a practice. At the time I wrote the book with Doug, judgement lists seemed fairly academic. However at this conference there was an entire talk dedicated judgement lists and at least three talks that casually mentioned relevance scoring methods (MMR, ERR, Precision@k, NDCG) which are based on the availability of judgement lists. Most exciting though, there seems to be a push toward using judgement lists to enable Learning-to-Rank. And Learning-to-Rank appears to be helping us to reach never-before reached heights with search quality.

The next thread was an apparent fascination with the notion of “vectors in search”. Three talks that I attended discussed exploratory techniques for taking embedding vectors derived from machine learning methods and indexing them into search engines. Two of these talks involved indexing images and one was about indexing text in such a way that you could achieve better relevance. Additionally, there was a talk about Vespa, a new technology that will allow tokens and vectors be indexed in the same index natively.

Individual Talks

Here are the highlights from several of the talks I attended.

Doug Turnbull: Keynote

I would expect nothing less from Doug than one of the most colorful, non sequitur talks I’ve ever seen. Doug did not let us down. His talk featured awkward prom photos, a prolonged discussion of scrapple, and even this slide:

That’s right “Turn silos into plungers so that we can protect sea turtles.” 🤔

But, through the intentionally non sequitur metaphors Doug’s keynote made a great point: The individual companies that use opensource search do a lot of reinventing of “table stakes” technology so that we have less time to work on the “secret sauce” of our own business domain. Doug keynote encourages the community to band together and build out these missing pieces so that less time is spent reinventing. Top areas of interest include:

- Search Analytics

- Standard ways of interpreting/using clickstream data

- Search beyond tokens

- Diversity & Serendipity, not just relevance

- Vector/Tensor math

Peter Fries: Search Quality: A Business Friendly Perspective

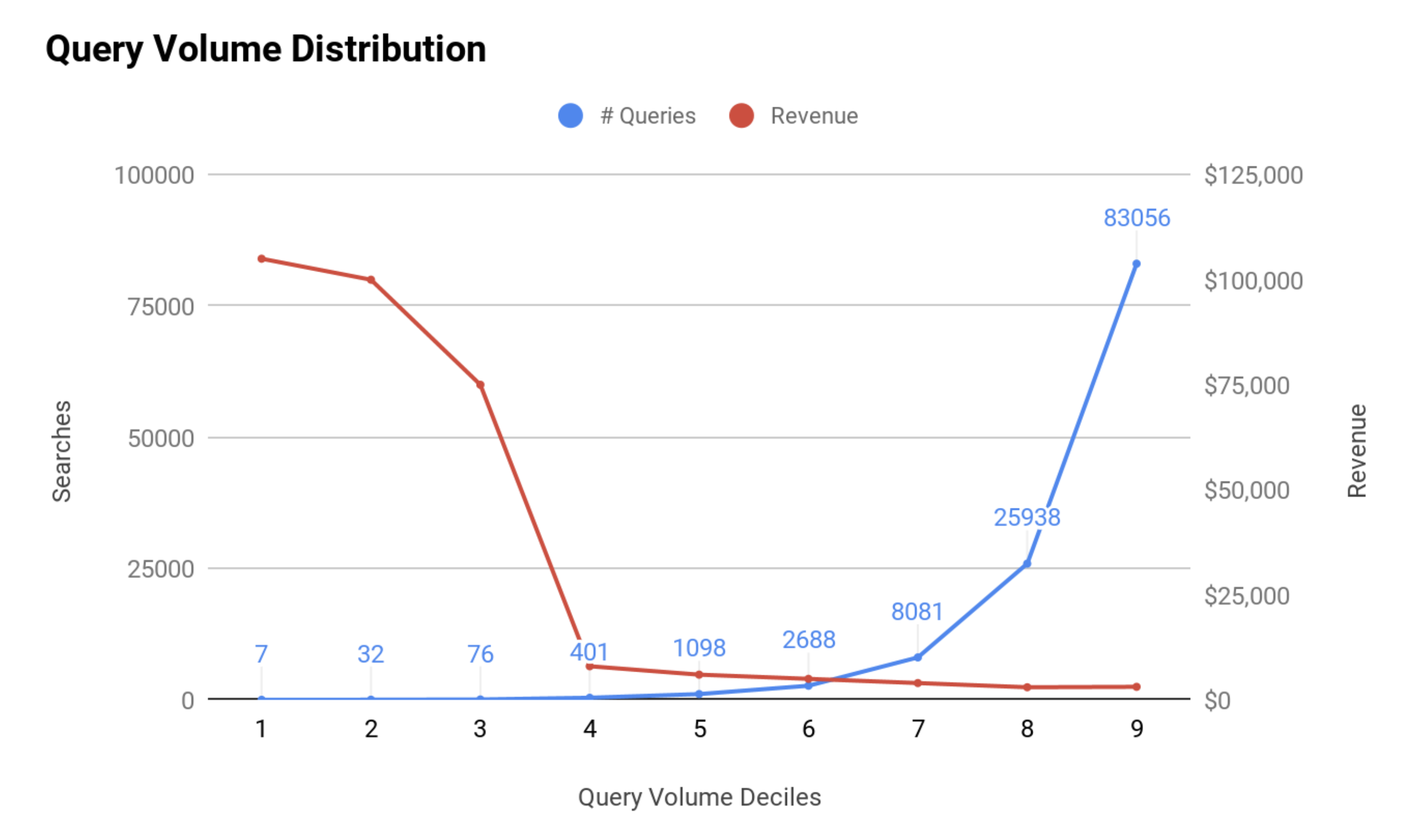

Peter’s talked covered the gambit of search considerations that you need to keep in mind when working with a business product owners. He laid out metrics that can be used to judge the health of the application from low-level relevance metrics (MMR, MAP, NDCG, etc.) to high level concerns such as user acquisition, retention, engagement and satisfaction. He also pointed out several business-related search anti-patterns. My biggest takeaway though was this graphic:

Look at how well this communicates so many ideas! We know from the blue line that 40% of our query volume is covered by 400 unique terms. And if you look at the area under the red line you see that this covers the great majority of revenue. This means your search problem just got a lot easier!

Chao Han: Use customer behavior data and Machine Learning to improve relevance

Similar to Peter’s slide above, the main point of this talk was to be aware of what constitutes the “head” and “tail” of your queries. You can think of this as another example of the 80/20 rule: 20% of your unique queries form 80% of your traffic - this is the head, and the other 80% of unique queries form only 20% of your traffic - this is the tail.

My big takeaway from Chao’s talk was that so many of the tail queries can be thought of as modified head queries. She provided a couple of great examples: First, many tail queries are misspellings of head queries. Second, many tail queries are augmented versions of head queries. For instance if “nike shoes” is a head query, then “red nike shoes” is a modification of that head query with the modifier “red”. Chao goes on to show how Lucidwork’s Fusion product provides an easy-to-use dashboard that ingests query logs and alerts the relevance engineer of these situations. The relevance engineer can then opt to automatically rewrite these modified head queries in order to improve performance. For instance, in the first example misspellings can be corrected. And in the second example modifiers can be queried against more appropriate fields. So the query: description:(red nike shoes) can be turned into color:red brand:nike^5 product:shoes^10.

Eric Bernhardson: From clicks to models, the Wikimedia LTR pipeline

Wikimedia has an enviably complex and interesting search problem: 300 languages, 4TB of data, 230M queries per day… And it just got more interesting: Wikimedia is now using Learning-to-Rank to improve their search relevance. Eric’s talk walked through the steps taken for collecting click data, turning that into training labels, collecting features, and then finally training the model. One thing that I found fascinating was the slide where Eric enumerated the features used in the model. These were divided into 3 categories:

- document-related features: popularity score, incoming link count, page length

- query-related features: per-field tf-idf, number of unique terms

- features related to both the query and the document: the match score for the document in each field (analyzed with and without stemming), phrase match on certain fields

And how did they collect the features for training? The aimed their Hadoop cluster at their Elasticsearch cluster and pumped production queries through it. I like!

In follow-up questions Eric discussed the outcome of Wikimedia’s work to move to Learning-to-Rank. It appears to have significantly improved search relevance and increased user engagement (more clickthroughs, less abandonment).

Elizabeth Haubert: Expert Customers: A Hybrid Approach to Clickstream Analytics

Judgement lists are set of tuples (query_text, doc_id, match_score). Judgement lists are a critical ingredient for several important things in information retrieval. For example, when your are measuring the quality of your search results using something like Normalized Discounted Cumulative Gain, you measure your quality against judgement lists. And Learning-to-Rank uses judgement list as an input for training.

In this talk Elizabeth did a great job elucidating the murky world of judgement lists. First she took a step back into history and told how judgement lists were first devised and refined in the early TREC conferences. I was surprised to learn that the first two attempts to build judgement lists (TREC-4 and -5) failed simply because human judgements are so subjective and because a user’s information need is so difficult to specify out of context. One of the big take aways from this section was that humans aren’t that dependable.

Elizabeth also talked about some techniques for generating judgement lists from click logs. For instance, with a technique called “query chaining” you watch for users that click on several items in the results sets. Every time an item gets clicked it gets 1 point, but every time an item is passed over and a different item lower in the list is clicked, then the passed-over item is given -1 point. When you sum up all of these points, for each item across all well-trafficked queries then poof you have a judgement list.

René Kriegler: ‘A picture is worth a thousand words’ - Approaches to search relevance scoring based on product data, including image recognition

Perhaps more than any other talk, René’s talk really got me thinking! He had found a way of using Inception v3 to represent product images in a search engine. René found that the relevance performance increased significantly when using this technique. Here’s roughly how it works - René runs every image in his catalog through Inception which then responds with a numerical vector describing what was in the image. Now as you might have read in my post about tokenizing embedding spaces, search engines aren’t particularly good at storing large numerical vectors so René approach here was to use a technique called random projections to convert the Inception vector into a binary encoded fingerprint for the item. Finally, René replaced the scoring function with a custom Jaccard similarity. The results were outstanding. A search for “laptop” that had previously returned laptop accessories (backpacks and cases) now returned actual laptops.

The first chance I get, I’m going to revisit my own ideas about tokenizing embedding spaces and see if I can apply some of the ideas I discovered from watching René’s talk.

Matt Overstreet: A Vespa Tour

Vespa’s been on my radar as a possible Lucene-killer ever since Yahoo open sourced it last year, so I was very glad to be present for Matt’s thoughtful tour of Vespa. The talk covered the features of Vespa and how to configure and run a simple search application. In principle you can build a search engine that works just like Lucene. But more than that you can build things that are more advanced than Lucene that combine both standard token-based search as well as vector scoring approaches. Most interestingly, you can even send complex sets of instructions to be run server side. This is huge! At Eventbrite one of our search-related page loads follows these steps:

- Get a set of “popular events” and as you return them also return an aggregation of the top categories in the user’s location.

- IF no results come back, then repeat the same search but with a much larger geo radius.

- Once we have those results, pick out the top categories and find the best events in each category.

See how much back and forth there is between the Elasticsearch server and the application backend? See how the logic for building and running queries is spread out between the query logic and the higher-level page logic? With Vespa you can do all this in one shot. You can define routines and ship all the logic to the server and then receive all the data in one big response. Wonderful!

But the problem I see is that if you want all this stuff - you’ve still got to build it! And that doesn’t seem trivial. Vespa apparently has something like TF*IDF scoring out of the box, but it doesn’t have tokenizers, stemmers, etc. for non-English languages. If you want it, you’ll have to build it, and you’ll be building it with Java. Also, being able to specify complex query logic is neat, but you can’t specify it in your language of choice. You have to specify it in (IMHO) a weird, JSON-ish domain specific language provided by Vespa.

Sujit Pal: Evolving a Medical Image Similarity Search

Sujit Pal is a very highly regarded blogger in our field and one of the “old guard” of search. (He used Solr at CNET before it was open sourced!) And Sujit is the second speaker that was interested in searching over images (ref. René above). In this talk, Sujit covered how to extract features from images, how to index the features, and how to measure search performance.

Regarding the features, Sujit covered global features such as color histogram, texture information, and the like. He pointed out that these features are often not good enough because very different images can have very similar global features. For instance desert sand dunes and ocean waves have very similar visual texture. The next feature type, local features, are things like the location of edges and corners in the images. These are pulled out with feature extraction algorithms such as Scale Invariant Feature Transformation (SIFT), Speeded Up Robust Features (SURF), and Difference of Gaussians (DoG). Finally, as everyone knows, Deep Learning has been kicking butt in image recognition tasks, so Sijut dedicated a couple slides to discuss the state of the art here.

Next Sujit went over several potential methods for indexing vectors. This is where my ears perked up, because Sujit offered more clues that will be helpful in my embeddings-to-tokens research project. Sujit investigated indexing sparsified features and added their values as payloads - but said that performance was poor above few hundred docs. He also covered a random projection-based method similar to René’s but basically dismissed it for search because the method was originally designed for detecting near duplicates rather than providing a smooth score from the most similar to the least similar documents. (I am actually hopeful that something similar to random projects will be the actual answer I’m looking for.) Another method, Metric Space Indexing involves picking out sqrt(N) reference objects and indexing the m most similar object ids as the document tokens.

Finally Sujit discussed how he evaluated his experiments using Precision @K and correlation metrics. The results indicated that there is more work to do, but they did look very promising.

Trey Grainger: The Relevance of Solr’s Semantic Knowledge Graph

This talk pointed out how some fairly simple tricks can turn a search engine into a sophisticated and intuitive analytics engine. Let’s say that you have an index full of resumés that an include a skills field and you want to determine what skills are related to “Data Science”. A very naive query can against this index can quickly provide you with insights - just query for all resumes that match skills:"Data Science" and then use an aggregation to get a list of all the skills also listed in these documents sorted by number of hits. The result will come back something like Programming, MySQL, Machine Learning, Data Mining, Analytics.

Notice that while these results do have good information - Data Science is similar to Machine Learning, Data Mining, and Analytics - there are also somewhat irrelevant results of Programming and MySQL. These spurious results are listed simply because they are so common. Trey showed us a neat trick called Foreground vs. Background analysis that can be used to remove these spurious results. The idea is to track the document frequency of the skills in the foreground search “Data Science”, and to compare this against the document frequency in the background of the entire corpus. So in this case, we would see that while both Programming and MySQL are popular among Data Scientists, they are also fairly popular among a wide range of careers and we could shift these skills further down in the list past more obvious matches such as Machine Learning.

The bigger takeaway from Trey’s talk is that with tools like Foreground vs. Background analysis you can turn Solr into a pretty dandy analytics engine. All you have to do is start chaining these queries together. For example, consider a request for “find all resumes associated with all the skills near to ‘Data Science’”. This becomes two requests chained together. First, perform the above Foreground/Backround request to get all the nearby fields. And next, query for all documents matching that broader ser of fields. Trey had several more complicated examples in his talk, make sure to check it out. And also, check this out - while Trey was at CareerBuilder he built and outsourced a nice API for all of this stuff.

Peter Dixon-Moses: Catch My Drift? - Building bridges with Word Embeddings

Peter’s talk was the third talk of the conference to strike near to my embeddings-to-tokens research project, but this time instead of using photos, Peter’s goal was to improve text search relevance by using features extracted from word2vec. This is an important goal. How often I’ve fretted that search engines are “just sophisticated token matching systems” and that they don’t really understand what the documents are actually about. Because of this keyword searches miss relevant matches simply because the document doesn’t contain the exact terminology of the keyword. If we were to do a good job of directly indexing the semantics of documents then we could overcome this problem.

The first part of Peter’s talk was an introduction to the word2vec algorithm. The algorithm is surprisingly simple. First you figure out the dictionary that you will use - this is something like the 10,000 most commonly encountered words after all stop words have been removed. Then you train a neural network to predict the middle word in a set of series of 5 words where only the first two and last two words will be known. The input to this neural network is 4 “one-hot” vectors of length 10,000 used to represent the first, second, fourth, and fifth words. The output of the network is a 10,000 unit soft-max vector representing the likelihood for the missing word to be any one of the 10,000 possible words in our vocabulary. Now here’s the part where we get the actual word2vec embedding: If you can train your network to accurately predict the missing word then the hidden layer right before the soft-max output encodes a pretty good embedding of the vocabulary. Then all you have to do to create the embedding is to match words in the dictionary to their hidden layer vectors.

Peter’s talk then goes into some of his own ideas about how these vectors could be indexed into search. The main idea was attaching the values of these vectors as payloads on labled tokens similar to what Sujit talked about. However, this again proved not to be a very efficient implementation. One neat idea came out of audience discussion - we might be able to keep documents encoded as vectors and actually off-source searching and similarity matching to our GPUs. How novel!

All the Talks

Do you feel sad that my blog post has now ended? Don’t worry, check out this link to see all (well, most) of the slide decks from Haystack. And be sure to check back to my blog regularly. I’m in writing more right now so you’re likely to find something new!