Neuroscience Penny Chat with David Simon

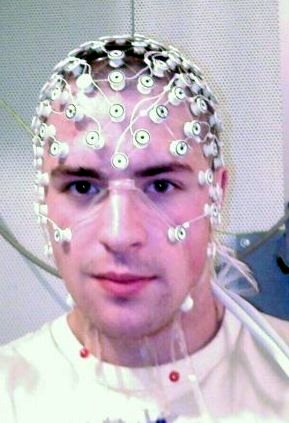

21 Jan 2018As many of my friends know, I’ve picked up neuroscience as a sort of side hobby. (Some people collect stamps, I memorize anatomical structures of the brain.) Last time I blogged about this was regarding my Penny Chat with Stephen Bailey on his work with MRIs. But this week I sat down with one of Stephen’s friends David Simon to talk about his research involving Electroencephalography a.k.a. EEG.

EEG - the “opposite” of MRI

I touched on this in my blog post with Steven, but EEG technology is in some ways on the opposite end of the spectrum from MRIs. The spatial resolution of MRIs is pretty good - on the order of a millimeter; but the temporal resolution of MRIs is rather large - on the order of several seconds. The speed of thought is much faster than the speed of an MRI.

For EEG the case is exactly the opposite. EEGs operate by picking up electrical signals from the firing of neurons. And while the full firing process of a neuron is on the order of a millisecond, the temporal resolution of an EEG is sub-millisecond or better. So EEG is as fast as you would ever need to observe the dynamics of neurons firing. The unfortunate pitfall of EEG technology is that the electrical signal produced by a single neuron is far to tiny to be picked up by and EEG. Rather, an EEG require thousands or even millions of neurons to be firing synchronously before the signal can be detected. As a result, the spatial resolution is quite low - on the order of centimeters. In addition, the skull is an unfortunately good electrical insulator, so this dampens the desired signal considerably, and makes it impossible to detect activity much deeper than the top layers of the cortex.

An EEG is Fine for Me!

Despite the fact that EEGs are limited in spatial resolution, I am still very interested in their utility for understanding how we think. Here’s why - meet the Lorenz Attractor:

The Lorenz Attractor is a type of system called a strange attractor. Well, backing up a bit, an attractor is a mathematical construct. It is a set of points that a dynamic system is destined to converge upon as time increases. (Checkout the Wikipedia page.) But with a strange attractor like the Lorenz attractor above, the dynamic system doesn’t settle down on any final position or loop, but instead can do strange things like flip-flopping between two patterns as shown above, or orbiting in a region of space without actually ever converging, also shown above.

I think that a strange attractor is a good metaphor and maybe even a good literal model for what happens in our heads as we think. Consider the thought of a cat. When you think of a cat, certain neurons in your head activate (probably the furry, purring one). And their activation triggers the activation of downstream neurons to activate. They then trigger further downstream neurons, etc. etc. Eventually, it seems apparent that the downstream neurons must loop back around and trigger the activation of the original neurons once again so that you get repeating, periodic patterns of neuronal activation. This is a thought. If the neural activations didn’t ever reach the starting neurons again then would we really be thinking about cats? No, our thoughts would be chaotically moving from one topic to another. That said, I don’t presume that we ever get back to exactly the original set of neurons, but just a large subset of the original neurons. So a thought then is a quazi-regular pattern of neuronal activations – a strange attractor.

That being said, consider what we’re measuring with EEGs. We can watch, millisecond-by-millisecond, the gross pattern of neuronal activations across most of the cortex. Sure, it would be nice if we could get to the resolution of individual neurons, but I suspect that our wiring at that level of detail is very different from individual to individual and therefore difficult to understand by any means (at least for now). And it would be nice to measure activity in the center of the brain, but much of the activity of higher cognition is actually happening at the surface of the brain. So, considering the constraints the Universe has laid upon us, an EEG is currently about the closest we’re going to get to actually measuring thought. And that’s exactly what I’m interested in.

David’s Work

During our lunch, David told me a bit about his Ph.D. research. David is using EEG to study the way that humans combine multi-modal sensory input to build a unified understanding of the world around them. David’s specific piece of research is with our ability to understand speech based upon a combination of visual and auditory input. For example, consider your experience when someone in front of you is speaking to you. You hear the sounds of their words and simultaneously you see the shape of their mouth. Without realizing that you’re doing it, your brain combines both signals unto a unified understanding of speech. Furthermore, the visual aspect of speech is surprisingly important. When a speaker turns their head away from you so that you can still hear them but you can’t see their lips, then your comprehension falls off quickly. David said that losing the visual input had the same effect as turning the volume down. (And this effect can be quantified.)

David’s research incorporates EEG by watching neural oscillations as he perturbs the visual and auditory input. His test subjects will watch a video of speech. As they are watching, David can delay or advance the visual signal so that the motion of the lips does not coincide with the sound. This causes changes in the brain patterns picked up by the EEG. This can in turn help us understand how our brains process and combine multi-modal inputs.

Things I Learned

David and I covered a lot of ground in our discussion. Here are a random assortment of neat things I learned during our lunch:

- You can fool the brain’s multi-modal processing. There was an experiment in which a subject was shown a blinking light that coincided with an audible beep. After being exposed to this pattern for a period of time, the subject had come to expect the light and the beep to always coincide. Eventually the light was turned off while the beeping continued. The subject of the experiment continued to perceive the light even though it actually was no longer present!

- The visual cortex apparently process input in frames. Consider an experiment in which test subject is shown a periodically flashing dot on a screen. If the frequency of the flash is timed to be the same as the frequency of the neural oscillations in the visual cortex, and if the phase of the flashing is adjusted appropriately, then the subject will be blind to the dot. Some how the dot is present on the screen when the brain isn’t recording the frame.

- Interestingly, experiments like above are somewhat frustrating to perform because, even though the brain is blind to the dot, the brain somehow knows how to realign the timing and phase of the neural oscillations so that they coincide with the flashing dot and the dot then becomes visible.

- Before our meeting I knew that learning was implemented in the brain as changing connections strengths between neurons. What I did not know was that a very large chunk of learning was actually in just throwing away connections. When you’re born, neurons are a lot more interconnected than they need to be. As you learn, these connects get paired way down. But this is beneficial, in that the brain is becoming much more efficient in its processing.

Thanks for the great discussion David! Let’s do it again.