Understanding Eigenvector Centrality with the Metaphor of Political Power

27 Jul 2014If you play around much with graphs, one of the first things that you’ll run into is the idea of network centrality. Centrality is a value associated with a node which represents how important and how central that node is to the network as a whole. There are actually quite a few way of defining network centrality - here are just a few:

- Degree centrality - This, the simplest measure of centrality, is simply the count of how many a connections a particular node has.

- Closeness centrality - This is the inverse of a node’s farness. Farness, in turn, is the sum of the length of the shortest paths connecting the node in question to all other nodes.

- Betweenness centrality - This is the count of number of shortest paths that pass through a given node.

But, my favorite measure of centrality is eigenvector centrality. Why? Because I invented it! Ok, ok… that’s not exactly true, but I did at least independently discover it. And the way I discovered it helped it stick in my mind ever since.

The Power of a Politician

There is a generalization that all politicians are merely empty suits and that they use their cunning social skills to advance their own status. One day I set out to investigate this concept - mathematically. I said to myself

Let’s model the power of a politician. Let’s assume that his power is not derived by any virtue or talent of his own. But rather, any power held by a politician is merely a function of those he is connected to. Afterall - it’s not what you know… it’s who you know.

Perhaps the most simplistic way to put this to math is to assume that political power is a numerical measure, and the power of a particular politician is proportional to the power of the politicians that he is connected to. In equation form this relationship can be represented as follows:

Here \(P_i\) represents the power of a politician and sum on the right hand side represents the cumulative power of all his buddies. The proportionality itself is represented by the value some constant \(\lambda\). What is the value of \(\lambda\)? Is it \(\frac{1}{2}\)? Is it \(\pi\)? We don’t know quite yet, but we will soon.

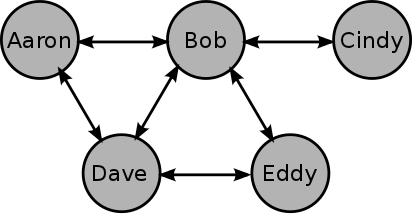

Now, based upon our assumptions, this equation should hold for any politician. So, let’s consider an example set of politicians.

Here we have 5 politicians, so that the corresponding political power equations should look like this:

(Here the subscripts refer to the individual politicians’ names.) If we solve this set of equations then we will know which politicians are stronger or weaker than the others. However this set of equations only applies to this particular group. We would like to generalize these equations to apply to any group of connected individuals. Let’s try using matrices and see if that helps:

Now the cool thing here is that the essence of the politicians’ social network is encoded in that matrix. If there is a 1 it indicates that the politicians corresponding to that row and column are connected. In graph theory, this matrix is called the adjacency matrix because it defines which nodes are adjacent to one another. In shorthand the above equation could be written as:

The astute reader will immediately recognize this as the classical eigenvalue problem. The catch, though, is that there are actually several solutions to the eigenvalue problem - which one should we choose? Fortunately, we are able to place an extra criteria upon the solution which will identify the unique solution. Political power as defined above only makes sense if it’s a positive definite value. And even more fortunately, the Perron–Frobenius theorem states that any real square matrix with positive entries will have only a single eigenvector which is composed completely of positive values (all of the others will be a mix of positive and negative values).

So, how do our politician friends fare? Here is the solution to the eigenvalue problem.

As you can see Bob holds the most power in the group followed soon after by Dave, while Cindy holds the least power in the group. Referring back to the diagram above, this result should agree well with your intuition as Bob seems well connected while Cindy is barely connected at all. (And, in case you’re wondering, \(\lambda=2.686\).)

The Eigenvector Centrality Metric

If you haven’t figured it out by now, this quantity that I’m call political power in the discussion above is none other than the eigenvector centrality of the politicians based upon their connection to one another. But is this notion of centrality actually useful? Yes, quite. Perhaps most obviously, the above analysis can be applied to any social network to help identify who the big players are. Want to know how you rank among your friends? Download everyone on Twitter within two jumps away from you, pull out the adjacency matrix and solve the eigenvalue problem - there’s your answer.

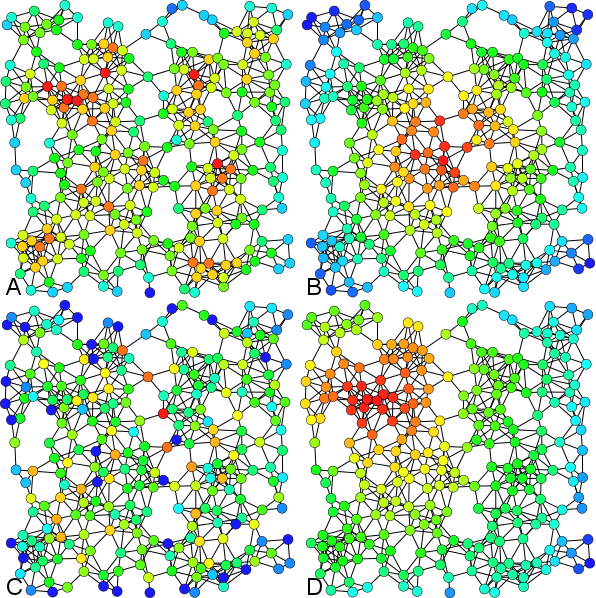

Outside of social circles, eigenvector centrality pops up again with text summarization. In this case, rather than looking at people in a social network, the analysis considers sentences in a document. In this case the values of the adjacency matrix are merely a measure of how similarly each sentences is worded to all of the others.

Any finally, the reason that you read this post at all is likely because you searched for eigenvector centrality on Google. In Google search, the importance of a web page is established in part by the Page Rank algorithm which is a variant of eigenvector centrality analysis described above!